June 1, 2023

All the things I can never show you

On body and control

For Charlotte,

For Sorcha,

For Alex,

For Belinda and Lu.

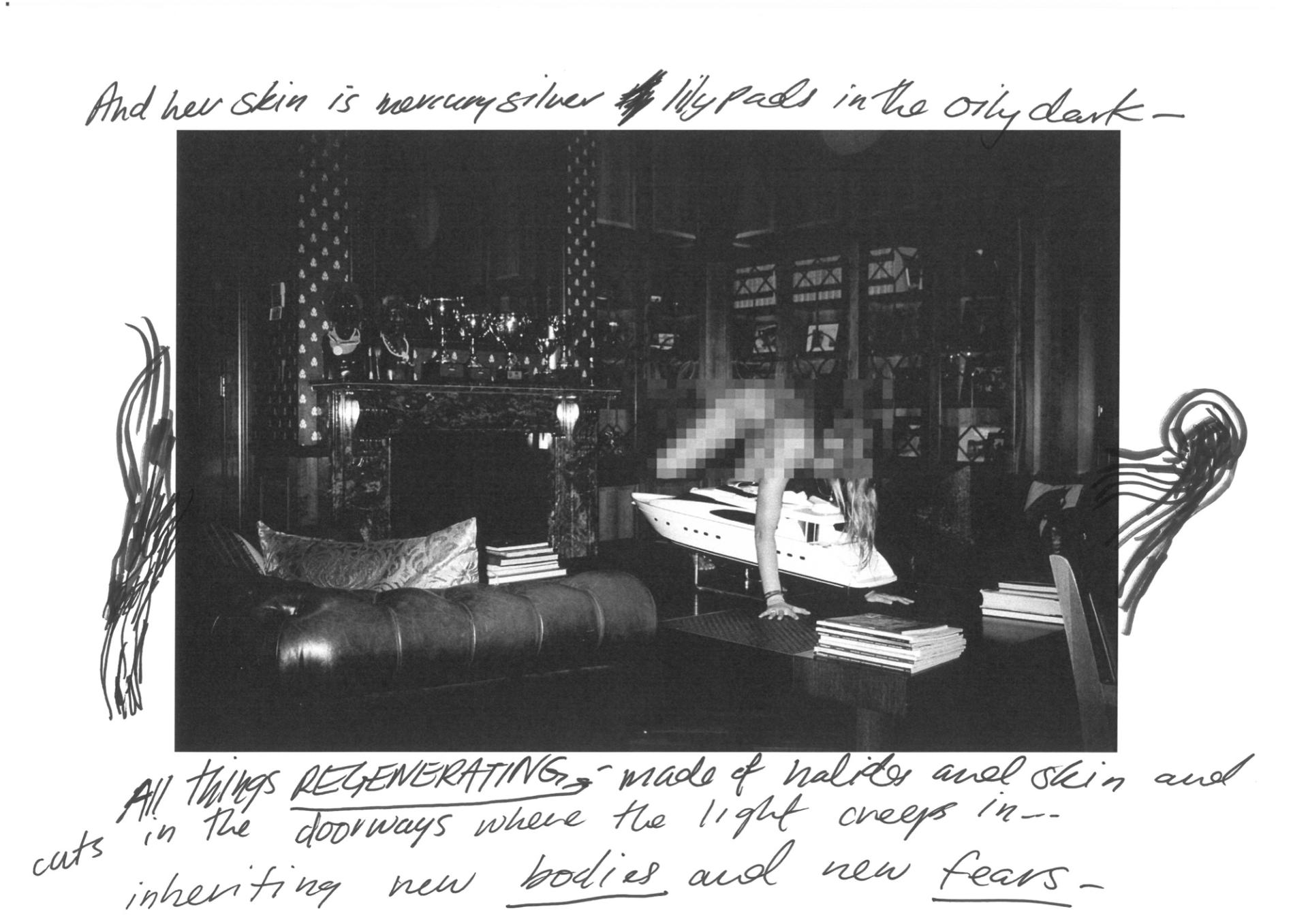

The library is dark, cushioned by rich-person furniture made with oily leather and deep buttons. There are trophies on the wall, boxes with thousand-dollar cigars stacked in them and a marble fireplace. Metallic-leafed symbols shimmer on the walls like lily pads in the black hardwood void.

On the low-lying coffee table is a miniature model of the estate owner’s luxury yacht—just in case he forgot about it. The estate owner is very old, but amazingly, memory is not something he struggles with. His big problem is blondes. Anyway, this yacht has a jacuzzi and can comfortably house 20 people, so even the miniature model is not that miniature at all. It spans about the length of your head to your pelvis—I know this because, above the yacht shrine, is my friend crawling over it, with one leg up, almost as though to piss on it. She is wearing nothing except a pair of blacked-out speed dealer sunglasses.

And there she is again—way up beyond the spiral staircase in the study. She is folded over the bannister in an amphibious way, her skin is mercury like the lily pads. We are observing each other through the blotted light of a chandelier the size of a car.

And now she’s crouched and shining at the indoor pool—where we first did MDMA. She is a terrifying nymph in the ecstasy grotto: all elbow and knee and wet, long blonde hair sticking to shoulders.

I spent my teenage years stoned in mansions with my mansion-dwelling friend, ripping bucket bongs out of antique vases and sitting on the beach. We’d look at Helmut Newton books until we’d worked ourselves into a frenzy, running around with pockets full of HP5 film in whatever new mansion the mother had bargained her reluctant, plastic affection for.

I lost all of these images. I had come to terms with this. I had taken up a Buddhist outlook on the whole thing and resigned myself to the idea that magical items like this are naturally averse to documentation. When I unexpectedly recovered them, all of this enlightenment left me. Fuck detaching from material posessions. I wanted to eat them, I was so relieved.

I spent so much of my developing years pointing a camera at my friends—their faces and transgressions, all their loves and their changes. I’d then develop those loves and changes by lovingly changing a negative to a positive, fumbling around in a room completely smothered of light and air, stinking of ammonium. My ears would be pricked to the sound of an old metronome, waiting and moving quickly, like some kind of wide-eyed nocturnal insect.

And here was the evidence! Relics of teenage devices. A message transmitted from 14-year-old me! I wanted the images published, I wanted them transmitted forward in time again, I wanted them out there—but this excitement was short-lived.

“How old were you?”

I looked at my partner with such confusion. My brain buffered for a few seconds—and then I got it. I couldn’t show anyone these images. I shouldn’t show anyone these images. It was not appropriate—illegal, perhaps. All things regenerating—made of silver halides and skin and cuts in the doorways where the light creeps in—forbidden.

I’ve had a body for 25 years now, and it’s been weird the whole time. When you’re inside it, you can sometimes forget that it’s a global experience. Photography forged a necessary alliance with me and my body from a young age because it was a fantastic way to exert some kind of control over the deranged wandering into the woods that was being a young woman. It woke me up to the possibilities of what a body can do.

Body-image is a word that’s been worn out, but to me, the factors of that word—its halves, image and body—make a formidable pair when done right, and embarrass themselves when done wrong. What image comes to mind when you read the word ‘body’? How is a body decided? A difficult question with a difficult answer.

All I have is the proof: a million photos of a million bodies (mostly my own).

There is a well-meaning, if not misplaced, call to shift the mainstream discussion of women outside of our body field—away from our physicality. I get this. But to me, renouncing the body also seems dangerous, and like a waste of politics. I find the vision of two young women—feral with inspiration, running around naked—to be incredibly freeing and reparative. If we are to believe in a collective story, which we must if we are to do better, then we must also pay special attention to its omissions, failings and detriments.

2024 was a dark night for Australia in many ways, one of them being the record-breaking body count of women slain by their spouses. Gendered violence was not leaving us. One headline about a woman who was murdered read: She died a hero, shielding her two-year-old son from her former boyfriend.

Beyond the obviously skewed language Australian media loves using to report such tragedies, I was specifically struck by the word ‘hero’.

As it stands, the utopian lovedream of a world where male-perpetrated violence never happens simply does not exist. As it stands, on any given day*, any man can make a hero of me. Any man can make a corpse of me.

My fixation on my hero/corpse body might just be a compassionate reaction to these pretty fucked parameters I am forced to survive in. Still, it also feels driven by an excitement to find more interesting, disobedient bodies; ones that rarely find an easy home in the mainstream.

And when it comes to the mainstream—I’ve done my research. Everything I’ve learnt about liminal spaces and the divine feminine has been against my will.

Many a time I’ve been cornered by the guy with spiderweb tattoos at art openings, and many a time he’s told me that he takes tasteful 35mm of the female form. He’s shown me his Instagram account. I’ve stopped myself from knocking the plastic cup of craft beer into his face and informing him that I am, in fact, female and I do have a form. But also an idea, and $180 worth of helium balloons inflated in my office at home. They spell out the words ‘BITCH WIFE’ above my desk. I write stories about an ancient fish underneath them. The giant reflective letters terrify my dog for some reason I don’t understand, but he’s just going to have to get used to it.

I’m aware of what 14-year-olds are doing on the internet right now, and I don’t find it an improvement upon the turbulent, untethered, often disturbing story of girlhood I captured with my camera. The prevailing online culture seems far more sinister and far less sincere. There is a similar reaching and looking around, but it still falls short.

Back there in the mansion, I remember feeling as though we’d inherited something. To inherit something is to not realise you have it until you can use it; like wealth. We inherited a new body, new fears.

***

From the ripe age of 16, I was spending time with my friend Alex. Alex is a horticulturist and a photographer. A true artist—the laughing, astonished kind you thought didn’t exist. When I met her she was always in a loose button-down shirt with a pair of secateurs in her jeans, and we’d be talking over a dining table in Coopers Shoot, cluttered with a million terrific things: a constellation of orchids, table lighters, film canisters, scribbled words on napkins, receipts and envelopes.

At this table we would discuss…I can’t really summarise the things we would discuss. We spoke about everything. Everything except status and money. Mostly sex and plants—and we aren’t perverts—these things go hand in hand more than you think.

Alex would hand me various fronds, spadices and branches while I crept around her garden, channelling a sort of magical green photosynthetic energy, and she would take photos of me doing this. I didn’t realise it at the time, but this experience counteracted many evil things I was at risk of: disordered thought, self-loathing, disenchantment.

The older I get, the more the importance of these encounters in the garden is revealed to me. Memories of them live deep in my mind. When Alex took these photos of me, I saw an irresistibly different way to live. I saw it squarely and straight on—squinting, squatting, usually with a cigarette balancing in my fingers or lips. I was not a woman, I was a Strelitzia nicolai. I had branches, not arms. Roots, not feet. I could germinate.

I learnt that bodily freedom has less to do with politics than it does with mutation and adaptation. My body suddenly did not have to always be taking another step in the long, arduous march towards actualisation or liberation (whatever that means); it could just be a system of nerves, vessels and seasons. I could give up on things that cost me too much energy. I could let them wilt and drop from me.

The plant projects were undertaken with great conviction and intelligence, and executed so perfectly in an environment that was so safe and beautiful. Vines and flowering plants climbed over boisterous palms, signalling each other with pheromones and colour.

If one of those 35mm dudes had walked into the house during one of our gin-fuelled discussions at that cluttered table, he would have dissolved into the humid, feminist air like a giant Berocca—I can tell you that much. Once reanimated, he would leave the house with a severe aversion to cameras and a sudden interest in landscape design. He’d go home and tell all his housemates, “Hey guys, all these Pulp Fiction posters don’t make us look as cultured as we thought.”

Have you ever woken hungover with adventure in your heart and thought, “I solved a great secret of the universe last night, but I’ve forgotten what it was?”

I often play a mind game where I encounter a person and ask myself, “What if they had an Alex from the age of 16 to 20?” In what ways would their thoughts be more tangential? Would they have solved the secret too, if only for a night? Would they be more willing to let themselves be complicated—perhaps even permanently so? Who would they be if they knew about plant signatures and cigarettes in the garden?

I do this likely because I don’t know who I’d be if I weren’t made aware of these things. I’d be incredibly disembodied. And way less fun.

Somewhere out there is a man with a hard drive full of myself—images of me. Me in a cane field. Me, smoking weed. Me, scowling. Me in bed. Me in overalls, looking at the sunset while I process the demise of our relationship. Me swiping at the camera, “Stop! I’m reading!” Me, psychically commanding him through the camera to put it down and kiss me; I’m transmitting this thought by refracting it through the lens and bouncing it into his mind through the pupil in his freckled left eye. And I’m doing almost all of these activities at least partially nude—sometimes in overalls.

I say all this to wager that nudity, although prevalent, is not the naked thing about me in these images. What feels more exposing is the capturing of this younger version of myself—her universe so centred on seeing and being seen. So eager to do both.

The direction of my eyes tells you more than my naked body ever could. If you look closely (which you never will), you’ll notice that my gaze was never centred. Even when I was sleepy, even when I was scowling—my eyes were always somewhere beyond the camera—looking for something else. Or in this case, someone else.

Being able to retrospectively visit this emotion is an incredibly strange, almost narcotic experience. Whether this is the psychological power the images were intended to hold, or whether they were just made to focus on the young, carnal body, contaminated by sex and love, is a whole other thorny conversation.

Story and words are so important—this is not just me being whimsical. Words are not ornamental; they have consequences.

I’ve noticed that we mostly speak of the female body as something that can be consumed, spoiled, martyred, poisoned and used. I know this is a body-story that many people need to hear. I remain far more interested in the body that is crawling around on all fours in the garden. The body that is mineral. The body that uses its teeth to open things. The body that will sleep in until 10am every day if you let it. The body that gets off. The body that is ravenous—and isn’t orthorexic in this appetite either.

It is a strong body that pulls things up from the root and can metabolise an ambitious amount of psychedelics; this is the body that puts things inside of it! Narcotic or otherwise (you get the joke). It definitely isn’t working to preserve itself or its virginal qualities.

I am interested in the body of adventure—a body disobedient to reason. Something that isn’t found but, rather, is doing all the finding.

I can see this fugitive body in the teenage images of my friend draping herself around the mansion. I can see it in Alex’s photos, always. I can see it in the aimed gaze of a younger self on that hard drive.

Hero or corpse? Dead or alive?

Does it have to be either/or? Haven’t we learnt that the answer is to always demand both? Should we tell one story without telling the other? Should we speak on womanhood and not talk about how we got there? Should we break our silence on the hardship but not the weirdness? Does this redaction leave us with a database of body-stories told with the language of violence and trauma, rather than adventure and desire?

For now, I’ll just have to stick to describing all the things I cannot show you.